Abbot Transition: A Reflection

July 1, 2023

by Wendy Egyoku Nakao

by Wendy Egyoku Nakao

The ritual of changing the Zen temple Abbot is called “Ascending the Mountain.” Rituals contain the energetic imprints of our intimate relationship to both the spiritual and material realms. They occur in liminal time when the lenses through which we see, hear, and feel are opened wide. During Ascending the Mountain, we experience continuity in the midst of impermanence; the enfolding of past, present, and future; and gratitude and service embodied in all that has been created together. This ritual marks an important passage in the life of a Zen temple/training center.

Mountains have long held a unique place in the Zen umvelt. There are the actual mountains—remote, imposing, and powerful—on which a temple is built in a secluded spot away from the machinations of the world. Be that as it may, Great Dragon Mountain is a small hill in the midst of Koreatown, Los Angeles, one of the densest neighborhoods in the United States and the densest in Los Angeles County. During my years as abbot, I took as my koan (and my inspiration) the old Chinese proverb “…the great hermit lives in the city.”

Integral to the Zen tradition are mountain hermits who master “the matter of extraordinary wonder” through “sitting alone on Mount Daiyu.”2 There is the mythical Mount Sumeru situated at the heart of Buddhist cosmology. Remember when a monk asked Master Unmon, “Not a single thought arises: is there any fault or not?” Unmon said, “Mt. Sumeru!”3 In Fukanzazengi, Dogen Zenji himself instructs us to sit immovable “like a big, rocky mountain (gotsugotsuchi).” Such mountain-like stability enables us to be fluid in the midst of ever changing circumstances, being able to respond in beneficial mutuality amidst the relational dynamics of any situation. Our mountain-dwelling ancestors left us these pearls. How do you too emanate steadiness in the midst of life’s vicissitudes as hermits living in the city?

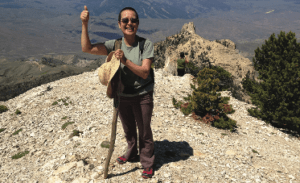

Roshi Egyoku at the top of Heart Mountain in Cody, WY.

The very presence of mountains evokes spiritual forces with which we spiritual seekers engage. As a child I lived with the primal forces of Mauna Loa on the Big Island, Hawaii, the home of the fire Goddess Pele sacred to indigenous Hawaiians. From my home on the Puget Sound, Mount Tahoma (Rainier) towers to the southeast, the ancestral homeland of seven Pacific Northwest tribes. On a pilgrimage, I climbed Heart Mountain—rising over 8,000 feet from the Big Horn Basin in Cody, Wyoming—a silent witness to the Heart Mountain concentration camp where Japanese-Americans were imprisoned during World War II. The most compelling spiritual-mountain forces that I have encountered, however, were those on Great Dragon Mountain during the nearly forty years that I lived there.

“…the great hermit lives in the city.”

Mountains symbolize the challenges of a spiritual path—the steep, rocky ascents, the turbulent stream crossings, the deep valleys and seemingly endless plateaus, the fog-shrouded peaks. The heat and cold, the winds, the brambles and lack of clear paths through the thickets of the self. We are focussed on reaching the mountaintop. Once there, the boundless vista of awakening reveals the widest and deepest possible views. There is exhilaration after a long struggle, but alas, we cannot remain at the peak. The descent beckons. On the way down, we may find ourselves speeding up, relaxing our attention as a sense of knowing arises. It is documented that most car accidents happen near one’s home, so watch out! The ego is sticky; habitual conditioning reasserts itself over and over again.

Mountains are both a symbol of the spiritual journey and of ultimate reality itself—of Thusness, the Here-and- Now reality. In Zen training, we learn to weave the threads of non-dual wisdom and compassion throughout our daily lives to liberate and benefit all beings. These are not idle words. How do you create life-giving relationships with your partner, children, co-workers, friends, strangers, and acquaintances? You ascend the mountain of the self; inhale the open vista of no-self; and descend back into the turbulence of everyday life. How do you embody the spirit of service from the vista of “no one who serves; no one to be served, no service?” Having been on the mountaintop, new questions arise: How do I need to be present in my life? Who will I be present as? These life-affirming questions are seeds which we water every day. We are no longer absorbed in the workings of the small self; rather we are dynamically engaged in mutually beneficial inter-relating moment by moment.

Another way of considering the dynamics of mountain climbing as spiritual awakening is through the lens of the vertical and horizontal dimensions of life. Ascending is the vertical: the inherent emptiness of all things. Descending is the horizontal: living life unreservedly, flowing freely in the thick of the everyday, creating buddha fields by flexing the muscles of relational virtuosity. In a teisho on the Blue Cliff Record, Case 32, Yamada Koun Roshi, our Dharma uncle, holds his teaching stick and says that as you engage Mu, “…you go deeper and deeper just like this stick rising gradually from a horizontal position and becoming vertical. That is the point of the ‘great death.’ Senior monk Jô (the monk in the koan) is now precisely at this point – his mind being empty, his intellectual functions have come to an acute halt. ‘Ten thousand activities are thoroughly scraped out.’ At this particular point one more movement is needed, like this (moving his stick slightly from the vertical position), in order to come over here. To be fixed in this vertical position is a fatal error; you need another leap forward. Then all things open up – it’s the ‘great resurrection.’ ”5 Descent is a leap back into life, into the marketplace, into the city.

“…you go deeper and deeper…”

Zen practice now begins anew: we are living in the nexus of the so-called vertical and horizontal. We steer clear of the old ruts, moving nimbly as we engage the practice of creating Buddha lands right where we are. Having seen the view from the peak, the everyday world is no longer seen as the world of difficulty or suffering, but rather as the world in which we now create an enlightened everyday life. Manjusri, the Non-dual Wisdom Bodhisattva residing on Mount Wu’tai, whispers to us now: your task is to become Manjusri in the midst of your everyday life; to create Mount Wu’tai in the very spot where your feet touch the ground. When you reached the mountain peak, you realized that the thread you followed is no-thread at all; now having descended the mountain, you weave the no-thread for the benefit of everyone. The Sangha Sutra says, “the thread of emptiness leaves nothing unstrung.” The poet William Stafford illuminates the thread in his poem “The Way It Is:”

There’s a thread you follow. It goes among things that change. But it doesn’t change. People wonder about what you are pursuing. You have to explain about the thread. But it is hard for others to see. While you hold it you can’t get lost. Tragedies happen; people get hurt or die; and you suffer and get old. Nothing you do can stop time’s unfolding. You don’t ever let go of the thread.

Zen mountain climbing—ascending and descending the mountain—is not the exclusive realm of abbots. Rather, it is an activity for all of us as we engage the Zen journey. The question bears repeating: Who do I need to show up as to create an enlightening environment right where I stand? This is a question for each of us, every day, in every situation. Whatever you have realized until now, how do you roll that into your conduct so that it is not an untethered, disembodied insight? Right this moment, does your presence—your behavior—reflect that, embody that? Challenge yourself to try on a new behavior; challenge yourself to not succumb to the habitual ruts of numb or dumb. The awakened life is not out there to be found; it is for you and I to create the here-and-now reality, moment by moment.

The one who sits on the Abbot’s Seat especially embodies this spiritual journey. As much as the question: “Who do I need to show up as to create an enlightened environment right where I stand?” is a question for each of us, it is even more so for the one on the Abbot’s Seat. I call this mysterious activity “mischief-making.” Indeed, there is great opportunity for mischief-making on the Abbot’s Seat, so let’s make good mischief together. In my years as Abbot, I found that one of the most powerful aspects of ascending the mountain is that the abbot training calls forth acute awareness—there is little room for self-absorption. One must shift and submit to the great Here-and- Now reality; to infusing wisdom and compassion as the response to all situations. How can I respond to the needs of others in a way that decreases suffering and brings about increasingly liberating ways of relating? How responsively creative and fluid can I be? This indeed is great mysterious mischief-making!

When I ascended the mountain in 1999, Roshi Bernie, my beloved teacher and abbot predecessor, told me: “Everything that you have done up until now is the ascending. Now all that you will do as Abbot, that is the descending.” In other words, it is time to put your shoulder to the wheel, the time of selfless service to the Three Treasures. One is claimed by the mountain, claimed by the seat, claimed by the energetic mold of abbot.

“Challenge yourself to try on a new behavior.”

This Spring at the Great Dragon Mountain/Buddha Essence Temple, the fourth abbot Sensei Kyobai Faith-Mind Thoresen descended the mountain and the incoming fifth abbot Sensei Baiten Dharma-Joy ascended. When Sensei Faith-Mind ascended the mountain in 2019, she said that she would serve as a bridge for four years from my tenure to whoever comes next. I thank her from the heart for her exemplary effort and service. I wish her deeply restful days of self-nurturing and restoration. Four years ago, there was no indication of who would arise to fill the Abbot’s seat. I am deeply grateful that Sensei Dharma-Joy matured and emerged as the fifth abbot. I express my deepest gratitude to him.

In contemplating the long years of Zen training of both of these Stewards, we see clearly that Zen is a life of service. The Mountain Seat itself is a seat of selfless service—a seat of abiding gratitude and grace. In particular, on this occasion, we all anticipate how the vision of the ascending abbot will enhance —complement and build upon or even dramatically alter—the vision of his predecessors. I look forward to seeing how Zen training unfolds, remaining true to essential awakening and the creative and skillful ways that will arise to meet the needs of the moment. This is the golden activity of our lineage. The work, however, is not so much about transmitting legacies of the past masters, but rather for each of us to personally exemplify awakening, to suffuse the very places where we sit, stand, walk, and lay down, with the wisdom and compassion of the buddhas for the benefit of everyone in our daily life and beyond. In this way, the great hermits create buddha lands in the city.

May the Great Dragon Mountain live for 10,000 years.

Thank you for your practice.

Roshi Egyoku Nakao served as ZCLA’s Abbot from 1999-2019.