2022 Bearing Witness to Racism in America Retreat

July 1, 2022

Four Sangha members reflect on their experience at the Zen Peacemakers International retreat.

Four Sangha members reflect on their experience at the Zen Peacemakers International retreat.

Valerie Richards

Do you remember when you first learned about slavery in the United States? Do you remember how you felt? I do. My family had recently moved to Miami, FL. I was in fourth grade. I attended a Catholic School where I was one of three black kids in my class. I felt embarrassed and confused. In eighth grade, I was the only black student in my class.

My teacher wanted to have a debate on the pros and cons of slavery. My mom was livid. She knew that

my knowledge of slavery was extremely limited. Both of my parents grew up in the segregated South. My mom recognized for many reasons that my teacher was a racist. What a dilemma. Perhaps your experience of learning about slavery was different but what is your understanding of how and why it occurred? What are the present-day ramifications?

Attending the Bearing Witness Retreat on Race allowed me to experience the places that I had only seen on television or read about. I thought that the retreat would be the culmination of years of study both in and out of the classroom. I was wrong! I must return to Alabama for an extended period of time. The history there is important because it sheds light on why issues like voting rights, gerrymandering and women’s reproductive rights were and still are rights that we should not let slip through our fingers.

As I walked through the Legacy Museum and the Lynching Memorial, I realized that what I read in the history books was only one side of a very complicated history. I learned that while black people were lynched it was because they had engaged in some “inappropriate action,” i.e. being accused of rape, theft or some other crime. While at the Lynching Memorial, I realized the arbitrariness of the decision to lynch. Much like the Coliseum in Rome, lynching was a “spectator sport” for white men, women, children and communities who participated in crowds as small as two and as large as 10,000 in the taking of a life without a trial or concern for the pain inflicted upon black families and communities.

I would encourage those who are truly committed to social justice to attend this retreat in the future. I realize

that it is easier to keep the blinders on—but at what cost? As I stood before the imaginary waves of the Atlantic ocean in the Equal Justice Initiative Museum, I thought about my ancestors who toiled and labored to help to make this country prosperous. This retreat highlighted why the generations before me fought so hard to obtain our right to vote. It can connect the dots for those who are ready to see.

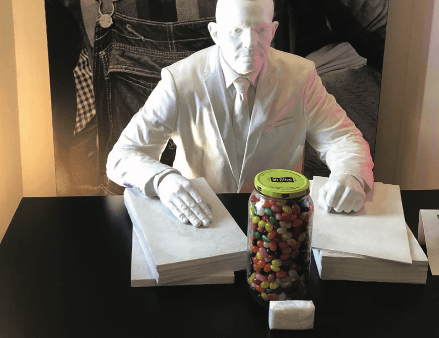

Black voters were expected to know how many jelly beans were in the jar and how many bubbles the bar of soap would make in order to vote. (Photo by Valerie Richards)

Sacha Joshin Greenfield

Sacha Joshin Greenfield

I initially hesitated to go on the retreat because I thought, “There’s so much racism to bear witness to right here in Koreatown, yet I avoid looking at or addressing that racism. Why am I flying to Alabama to bear witness to the racial history of the US, when I’m not addressing the racism in how I relate to my neighbors?” In spite of this, I had a very strong feeling: “I must go.” I later realized that this is an opportunity for me to take action and face my discomfort in addressing racism in my daily life. But the question continued to be present for me—why am I going to this “other place?”

During the retreat, I often felt, “There’s something wrong with me, because a lot of this isn’t affecting me.”

This is how I experience “white numbness”—the part of my conditioning as a white person where I dissociate from uncomfortable situations involving race. Since returning, however, vivid images and feelings from the retreat have stayed with me, like the lynching memorial in Alabama. One morning, sitting at ZCLA after returning, I suddenly felt the whole memorial: the place, the sculptures, and the over 4000 lynched human beings — and their deep suffering and Trauma — as one Whole. The meaning finally penetrated, as though whatever the memorial was trying to teach me found a way in at last after three weeks.

Since returning, the place of the retreat has not left me, and I have realized those places in Alabama where we bore witness are not somewhere else. The trauma of racism they hold are actually here in my body, and I must continue to open myself to that and bear witness.

Jitsujo Gauthier

Of course, there will be resistance. Whenever I step out of my comfort zone, a committee of hungry ghosts, Buddhas and Bodhisattvas gather in my mind to offer various concerns. During the retreat, I practiced staying in my body, being completely present, and trusting just this. I contemplated: where is the edge between bearing witness and being a tourist? Am I seeing this experience as transactional? Do my expectations and disappointments relate to my privilege, desire to fix, or difficulty feeling pain? What are my internal responses and assumptions of Black folks, Asian folks, Middle Eastern folks, Mexican folks, Latinos, white folks, etc.?

Upon returning, the shooting happened in Buffalo. I thought about the young white perpetrator, and the spectacle of this shooting as another hate crime. I recalled the photos of public lynchings and newspaper articles that advertised lynchings as barbecues in the Legacy Museum.

I remembered the montage of countless Black boys and men shot for running, standing, eating, driving, walking. Granted, the Buffalo shooting was not reported as a fun spectator sport, but there was a knowing that if that perpetrator was a young Black man, the police would have shot him. I wondered, what caused the police to not shoot this young white man? Was it a stereotype of him as a “good ‘ol boy” who strayed from the path and just needed to be set straight? If so, how do we undo such stereotypes? Even “good stereotypes” seem to be causing harm here. There is mental illness that is neither being identified nor addressed—in the case of this young white perpetrator, and in the many European-Americans who have dehumanized, stolen, enslaved, and killed countless people over time.

Another side is the stereotype of Black men as inherently violent and dangerous. The retreat demonstrated how this story was created and retold over time, conditioning all of us to believe it. For example, when I see the news, the thought arises: “well that young black man must’ve done something to be shot, he must’ve, right?” Bearing witness to racism in America is painful, but it is allowing me to see these ideas become hollow, unfounded. I see how both conditioned stereotypes perpetuate the justification of slavery, violence, incarceration, and domination, as well as our collective ability to ignore injustices. It feels important to continue bearing witness to both suffering and joy.

Geri Meiho Bryan

Geri Meiho Bryan

I went on this retreat to Alabama to look under the rocks of America’s racism and sit with all the exposed wormy bits underneath. I felt a calling that it was the work that I needed to do. I had no idea what I was walking into. I did not have any ideas of how things were going to go down. In Hunter S. Thompson’s words “I bought the ticket and took the ride.” I was not prepared for the actual experience of people of color as they went through the Legacy Museum. I overheard a woman of color crying and exclaim, “We were kidnapped and then enslaved!” The sobbing was inconsolable. Realizing America has been built on the commoditization of enslaved human beings is an enormity of injustice that is hard to fathom. This retreat was the starting point for me to step into witnessing my country’s racist past and current injustices. I have been complicit in the injustice by not asking enough questions and drilling down deeper into an uncomfortable truth. Reflecting back, my voice has changed. My heart has opened, and I vow to no longer look away. I don’t have the answers, but I am willing to ask more questions.

In Selma, I crossed paths with a mural artist, Tres, who sold his house in Birmingham and moved to Selma and vowed to cover the black belt (the southern part of Alabama that is currently economically depressed) in art. He had a few murals in Selma that were just purely whimsical. A conversation with the owner of the Airbnb we stayed at in Montgomery expressed that Montgomery is not what it once was; it has evolved and it’s looking at its past with a clear eye and informs what the city is today. She would encourage you to visit and see for yourself. It is grace that brought me to this retreat. I hope that grace brings me back next year.